In this post, I explore how AWS Billing & Cost Management Dashboards streamline FinOps, monitor service costs and create clear, shareable visual narratives.

(Also, yes – amazonwebshark has been around since 2021 and I can’t believe this is the first time FinOps has been mentioned – Ed.)

Table of Contents

Introduction

On 20 August 2025, AWS announced the general availability of Billing and Cost Management Dashboards. Before this, visualising costs meant flipping between various invoices and Cost Explorer windows. This new feature eliminates that. Users can now visualise and analyse AWS spending in a single view using custom dashboards, combining data from AWS Cost Explorer with Savings Plans and Reserved Instance coverage and utilisation reports.

As a long-time data professional and analytics geek, I loves me some graphs. And as someone who regularly uses Cost Explorer in various ways, I was keen to check this out. One thing led to another and this post emerged!

I’ll begin by examining the benefits of the new AWS Billing and Cost Management Dashboards and how to access them. Then I’ll build two dashboards – one in a standalone AWS account and another in my AWS Organisation Management account. Finally, I’ll examine how to share dashboards between AWS accounts.

Firstly though, I’ll be talking about FinOps, visualisation narratives and data storytelling in this post. These might be new concepts to some, so let’s start with some explainers.

About FinOps

FinOps is short for ‘Financial Operations’. It’s the practice of bringing together finance, engineering, and business teams to maximise the value of cloud spend. Instead of cloud bills being something only Finance is concerned with, FinOps makes cost awareness part of everyday decisions – both non-technical and technical.

FinOps isn’t just for accountants. Engineers can see how their services contribute to the monthly bill, Finance can track patterns and generate forecasts, and leadership gets high-level visuals they can view and share without needing to interact with spreadsheets and raw data. FinOps can also help during negotiations with service providers and cloud platforms, from SLAs to resource reservations.

Data Storytelling & Narratives

Visualisation narratives and data storytelling both focus on using charts and visuals to add context to raw data. They combine data, visuals and narrative to show both what is happening and why it matters. The goal is to create a unified message that moves from context to evidence to insight, rather than using isolated charts.

In cost management, this means structuring dashboards so visuals tell a story: a high-level view of overall spend, followed by the accounts or services driving these costs, and then the details that provide supporting evidence. This turns a dashboard into a coherent narrative that links costs to activity and business goals.

The value lies in this clarity. Narratives reduce noise, highlight what matters, and make cost information accessible to both technical and non-technical teams. They also reflect FinOps guidance on timely and accessible reporting, aligning with the AWS Well-Architected focus on continual optimisation.

Dashboard Benefits

AWS Billing and Cost Management Dashboards help support key industry standard cost guidance. An example of this is the FinOps Foundation‘s FinOps Principles, including:

- Enabling teams and account owners to monitor and manage cloud spend without relying on external teams or tools.

- Allowing centralised FinOps teams to highlight and promote key cost metrics consistently across the organisation.

- Providing real-time updates, ensuring accuracy and constant access without requiring data team oversight.

- Supporting collaboration between finance and technology teams to understand costs and their alignment with business goals.

AWS Billing and Cost Management Dashboards also align with the AWS Well-Architected Framework’s Cost Optimization Pillar goals. For example:

- Encouraging active and ongoing management of cloud costs, rather than end-of-month reporting.

- Increasing awareness of usage and expenditure to enable informed decisions.

- Making it simple to identify resources or services that may not be cost-effective.

- Revealing usage trends against demand to ensure resources scale appropriately without overspending.

- Showing long-term patterns to validate optimisation efforts and drive continuous improvement.

Additionally, sharing dashboards from AWS Organization Management accounts means fewer people need direct access to the account itself, supporting security best practices. And because Billing and Cost Management Dashboards are free to use and require no knowledge of Amazon Quicksight, they come with almost no technical or financial overhead.

Creating Dashboards

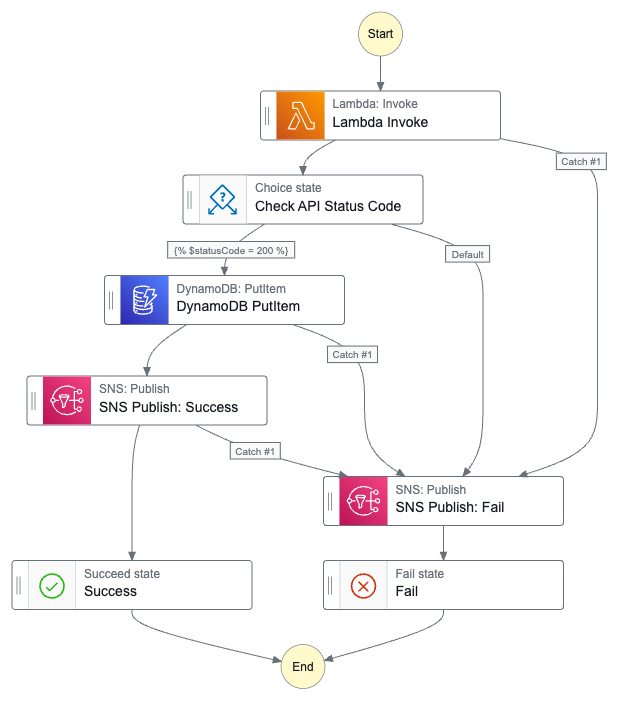

The new AWS Billing & Cost Management Dashboards are accessible via Billing & Cost Management → Dashboards:

The Dashboards console then appears, showing all dashboards by default and a tab for shared dashboards:

Finally, this is the screen for adding widgets to a new dashboard:

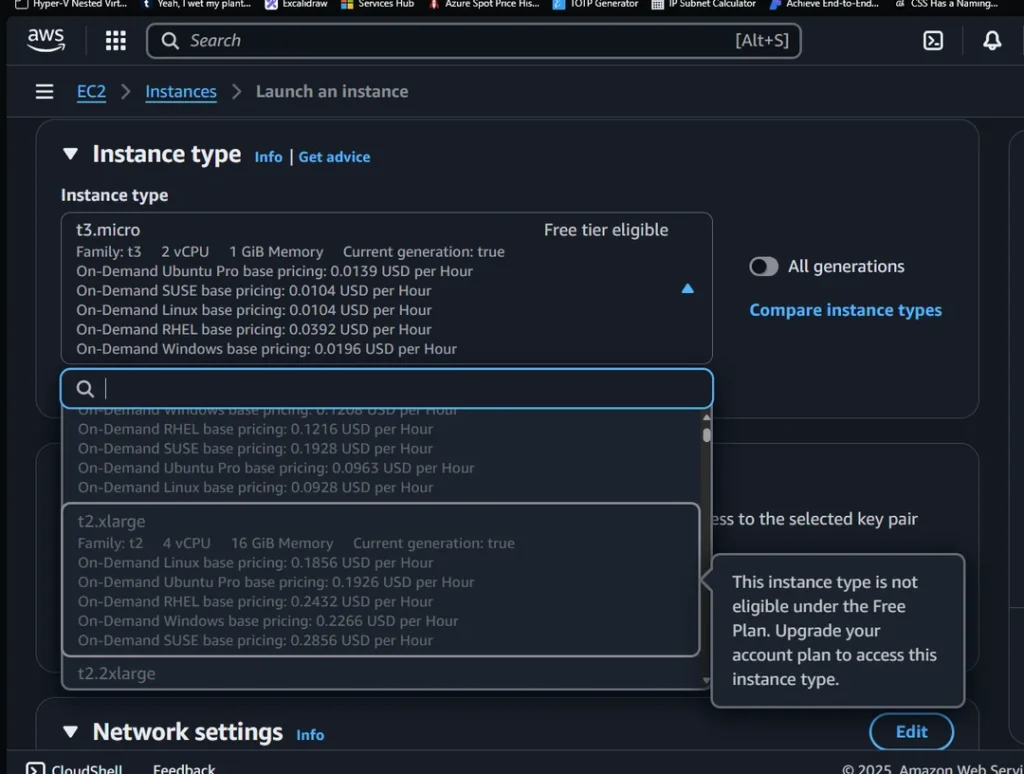

There are two types of widgets:

- Custom widgets for bespoke reporting needs.

- Predefined widgets for common use cases. These can also be customised as needed.

These widget types are explained fully in the AWS Cost Management widget types documentation. Having selected and positioned a widget, it can then be customised using the Cost Explorer UI and features, including filters, dimensions, and granularity.

(Aside – there are several widgets aimed at Reservations and Savings Plans. I don’t really use these in my AWS accounts, so you won’t see them being used in this post – Ed)

AWS Cost Explorer and Cost Management Dashboards use the same billing data but serve different purposes. Cost Explorer is ideal for digging into details, while Dashboards focus on building clean, repeatable and shareable views that fit into reports or presentations for technical and non-technical stakeholders.

When creating or editing dashboards, time periods can be set at both the dashboard and widget levels:

- Dashboard-level time periods apply temporarily to all widgets and reset when leaving or refreshing the dashboard.

- Widget-level time periods are saved with each widget and persist until changed.

Single Account Dashboard

In this section, the focus is on building a dashboard for a standalone AWS account. Using a mix of predefined and custom widgets, it’s possible to track costs at both the service and API operation level, reveal usage patterns over time, and spot trends that may indicate opportunities for optimisation.

Monthly Service Costs

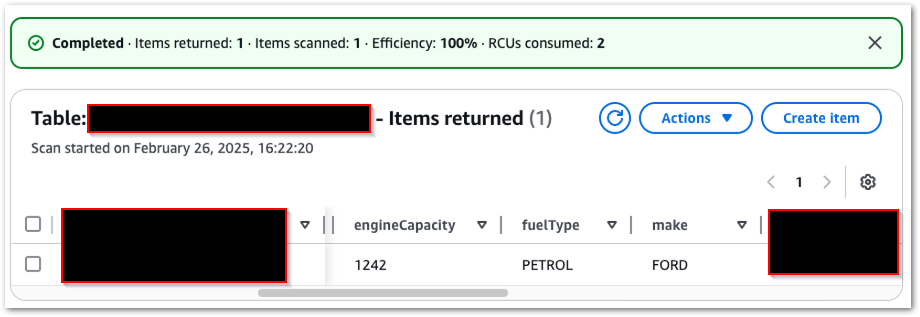

Let’s start with a predefined Monthly Costs By Service widget:

This chart displays six months of service usage, with S3 accounting for the majority and showing a recent downward trend. While there are empty sections showing service utilisation with very low or no cost, I’ve left the widget filterless in case that changes in future.

Daily Service Costs

Next, let’s include a predefined Daily Costs widget:

This is the default bar chart, and it’s not that useful here because it doesn’t tell me much. So let’s make some changes. This menu is available for all widgets:

Under Change Vizualisation Type, there are options for a bar chart, line chart, stacked bar chart and table. Given that I want to track my cost trends over time, a line chart is best suited here.

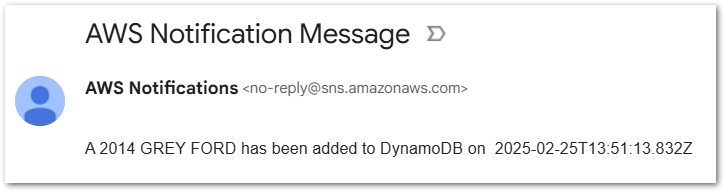

The Daily Costs line graph looks like this:

This still isn’t great as the regular spikes are off-putting. These spikes are a combination of Route53 hosted zones and Tax. However, as both these costs are only debited once a month, and at the same time each month (the 1st), they appear out of place here, as the spikes create an alarming-looking chart. In reality, these are standard events.

Looking back at the earlier chart, the biggest cost by far is S3. Let’s adjust the graph to analyse that by updating the Service filter to only include S3. A quick update of the chart’s title and description produces this:

This is much more helpful! Easier to read and comprehend, and has a clear message and narrative. Daily S3 costs in this account were around 20¢ per day from February to May, then almost halved in June and were under 1¢ per day by the end of July.

Spotting sudden drops like this is useful, as it can flag lifecycle rules kicking in, data movement between storage classes or workload shifts. Equally, a steady rise can indicate the need for lifecycle policies or changes in access patterns.

API Operation Costs

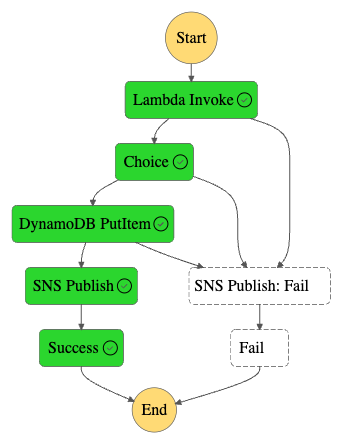

Let’s go deeper into the account spend with a custom Cost widget grouped by the API Operation dimension:

Urgh. Couple of problems here:

- The chart’s narrative is hard to understand as the bars are sorted by total expenditure across the entire time period of the chart. For example,

StandardIAStorageis huge in May, barely there in June and gone in July. And it’s not even in the July bars at all. Yet it’s always the first bar because it’s the biggest spend overall. Confused yet? - The legend confuses further.

No Operationis Tax – while this is correct within the context of the API Operation dimension, it doesn’t help the chart’s story. And Others is no help at all. - Finally, that axis is no use. What was the cost of

PutObjectin May? And how does it compare to July? No idea.

Given that I want to examine individual API-level costs here, a table is a better choice. It provides precise totals with no need for axis interpretation, shows a $0 spent as a value rather than the absence of a column, and eliminates the requirement to compress everything into a summarised, non-scrolling visual, thereby removing the vague Others legend and axis.

Finally, let’s exclude Tax from the Service filter (yes Tax is a service) and I get something far closer to what I want:

This dashboard allows me to track both monthly and daily spending, analyse costs by service and API operation, and identify any unusual spikes or drops. It simplifies monitoring trends, such as changes in S3 usage, and helps me pinpoint exactly where expenses are occurring. This way, I can quickly focus on areas that may require attention, turning detailed cost data into a clear and understandable overview of account activity.

AWS Organisations Dashboard

In this section, the focus shifts to dashboards in an AWS Organisation Management account. The goal is to track costs across multiple linked accounts, understand how AWS credits are being used, and monitor S3 Standard usage.

Note that the charts in this section appear slightly different, as they exclude my organisation’s AWS accounts. While the names are fine, the charts also include AWS account IDs, which I consider sensitive and prefer not to share.

Linked Account Costs

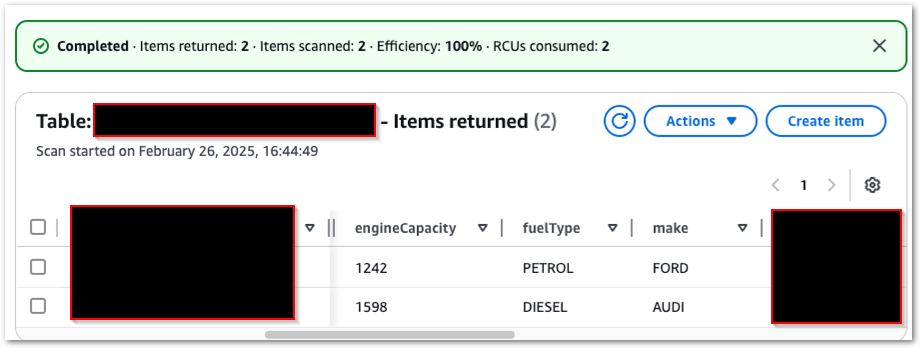

Let’s start with a default predefined Monthly Costs By Linked Account widget:

Ok so there’s a lot of empty space here. Although this organisation has existed for a while, it only began generating costs in May 2025. Additionally, the chart does not include any costs for July. This is because I applied my AWS Community Builder credits then, so future months will also follow this behaviour by default.

Let’s make this chart more useful by changing the date range from the last six months to the last three months and amending the Charge Type filter to exclude AWS credits, thereby showing my original spend:

As the July spend now dwarfs that of the other months, the axis makes the visual fairly useless. What’s July’s blue bar value? For that matter, what’s June’s green bar value? No idea at all.

Given that I want exact values, and that these values can be wildly different from month to month, this visual works far better as a table:

The monthly spend for each member account is now far easier to see.

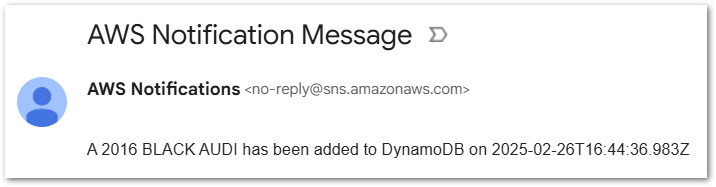

AWS Credits Usage

In the first chart I excluded my AWS credits to see my original spend. But it’d also be helpful to know more about my Community Builder credit usage. Am I burning through them quicker than anticipated? To what extent are the credits covering my AWS spend? And, given they’ll expire eventually, should I be bolder with my cloud spend to get the most out of my credits while I have them?

To visualise this, let’s make a custom Cost widget focusing on the Charge Type dimension:

This is already helpful but, like the first chart, a table is better here for precision and clarity:

And let’s update the widget’s title and description to communicate what is being shown:

S3 Standard Usage

Finally, I want to create an early warning system. When storing objects in S3, the default is usually Standard. There’s nothing wrong with this, and S3 Standard is a good choice for short-lived data.

However, it’s also among the most expensive of the S3 storage classes, and if multiple accounts in my organisation are using S3 Standard when they don’t need to, then I’m neither following best practice nor am I well-architected.

So monitoring my organisation member accounts’ use of S3 Standard is a good idea. This will measure when my S3 standing utilisation is trending upwards, showing me where to focus my optimisation efforts if they are needed. I can do this using a Custom Usage widget, configured with a Usage Type Group of S3 Standard:

As this value is being tracked over time, a line chart is more suitable:

I experimented with changing the granularity from monthly to daily, but I wanted to keep this dashboard for monthly reporting, intended for observability rather than alerting. That’d be better suited to a custom usage AWS Budget configured to monitor a daily S3 Storage: Standard usage type group.

This trend can be further tracked by adjusting the dashboard’s date range. The visuals below show cost data from 01 July to 25 August, showing a downward S3 Standard usage trend and my August 2025 costs up to that point:

This multi-account dashboard allows me to track monthly spending across linked accounts. It provides insights into how AWS credits are being used to offset costs and helps me monitor trends in S3 Standard storage across the organisation. With this dashboard, I can easily identify which accounts are driving costs, understand how credits are applied, and pinpoint areas where S3 usage may need optimisation. It transforms multiple streams of raw billing data into a simple, cohesive view.

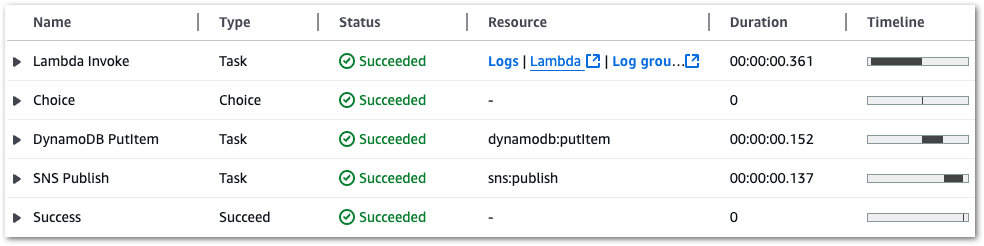

Sharing Dashboards

Once dashboards are created, they can be shared. Sharing allows teams, finance stakeholders, and other account holders to view or collaborate on dashboards without requiring direct access to the underlying AWS account. This makes it easier to align on costs, promote FinOps practices, and ensure visibility across the organisation.

Accounts can be shared both within and outside of an AWS Organization:

Behind the scenes, both sharing options are handled by AWS Resource Access Manager (RAM). If an active AWS Organization exists, then the dropdown list is populated with the member accounts. Alternatively, account IDs can be entered manually.

While this view is the same whether AWS Organizations is enabled or not, accounts not in an AWS Organization will see an error when interacting with this list:

As accounts are selected, their access can be set as:

- Can View: Recipients can view the dashboard but cannot make changes.

- Can Edit: Recipients can view and modify the dashboard configuration.

The selection process is very flexible. A single sharing configuration can include both internal and external accounts, and can assign these accounts to either permission scope. Accounts are added to the Added Recipients section as they are selected, showing which accounts can access the dashboard and with what scope:

These accounts will then view the dashboard in the Shared With Me tab of their Billing & Cost Management console. While users can view the dashboard layout and widget configurations, they don’t have access to the underlying data. Also, the data they do see is based on their IAM permissions.

Sharing dashboards enables collaboration among teams and finance stakeholders, offering visibility into costs while eliminating the need for direct account access.

Summary

In this post, I explored how AWS Billing & Cost Management Dashboards streamline FinOps, monitor service costs and create clear, shareable visual narratives.

As demonstrated, I’m already using this feature and am a very happy customer! I love how simple and expressive it is, and especially appreciate not having to manage any backend ETLs or pipelines. I am 100% the type of user this feature was built for, and it delivers exactly what I need to monitor, understand and communicate AWS costs across accounts with minimal effort.

I’ve got a few wishlist items. Exporting daily dashboard snapshots via SNS to Slack or email would be useful. This is a PowerBI feature that would work well here, especially since the data wouldn’t be shared – only a snapshot of the dashboard and a link to the resource. Support for CloudFormation and CDK would also make adoption and repeatability easier.

AWS Billing & Cost Management Dashboards make it simpler to build cost narratives, share insights, and track usage without the overhead of QuickSight or third-party tools. They are available at no additional cost in all AWS commercial regions.

Like this post? Click the button below for links to contact, socials, projects and sessions:

Thanks for reading ~~^~~