In this post, I examine some unexpected AWS Glue costs and design an event-based cost control process architecture.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Last month, I finished a series of data pipeline posts using, among other services, AWS Glue. During this series I made many discoveries – some more desirable than others. One such undesirable was a cost spike in early June! Not enough to trigger a budget alarm, but still higher than expected at that time.

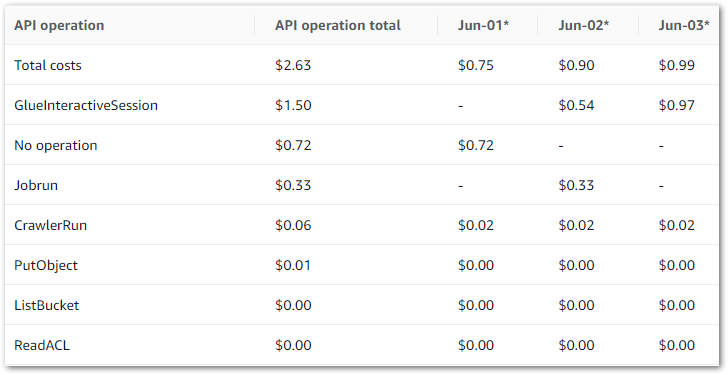

To Cost Explorer! These were the results:

Those Glue costs were…unexpected. While this doesn’t look like much, in contrast my entire May 2024 bill was $1.08. So June saw an almost 150% cost increase over just three days!

This post has two sections. Firstly, the Discovery section examines the costs in closer detail and considers potential solutions. Secondly, the Architecture section examines the decisions made for and the technical implementation of the chosen solution.

Discovery

This section examines the costs in closer detail and considers potential solutions. I’ll structure the cost analysis using three questions:

- How are the costs made up?

- What specifically is generating the costs?

- Why are the costs being generated?

The How

Question 1: How are the costs made up?

Firstly, let’s break down the costs. The earlier chart shows that Glue is the main cost driver – I now want to drill down into the API-level costs. I can do this by changing the chart’s dimension to API Operation.

This updates it to:

And the raw data to:

The main costs here are all Glue APIs, with the top two being:

GlueInteractiveSessionJobrun

No operation is tax – Ed

Jobrun was easy to account for, as I was testing some Glue ETL jobs at the time. But I was unfamiliar with GlueInteractiveSession, and as it was the biggest cost driver it became the focus of my ongoing investigation.

The What

Question 2: What specifically is generating the costs?

So what is the GlueInteractiveSession API? What does it do? And how does it accrue costs? Let’s begin with the AWS User Guide definition:

The interactive sessions API describes the AWS Glue API related to using AWS Glue interactive sessions to build and test extract, transform, and load (ETL) scripts for data integration.

https://docs.aws.amazon.com/glue/latest/dg/aws-glue-api-interactive-sessions.html

AWS Glue Interactive Sessions offer serverless, on-demand Apache Spark environments that work seamlessly with Glue ETL jobs. These sessions allow for the live development, testing, and enhancement of data processing steps and ETL tasks. They can easily connect to data from various AWS services such as S3, DynamoDB, and Redshift.

Interactive Sessions let users preview data without running full ETL jobs. This offers several benefits during development and testing:

- Data modifications are only temporary during an Interactive Session, protecting the original data from undesired and unintended changes.

- Jobs can be evaluated step by step rather than after each complete run, allowing for quicker development and testing compared to always executing the full job. And because of this…

- When testing ETL steps, interactive sessions usually use fewer resources than a Glue job, thus reducing costs.

Speaking of costs, Glue Interactive Sessions billing is similar to Glue ETL Job billing and is based on the following factors:

- Duration: How long the session runs, measured in seconds.

- Resource Usage: The resources consumed during the session, such as CPU, memory, and storage.

This all sounds good. So why is my bill so high?

The Why

Question 3: Why are the costs being generated?

So I now know that:

- The

GlueInteractiveSessionAPI is the main cost driver. - My Glue Interactive Sessions are linked to my AWS Glue ETL Jobs.

Let’s now examine why the GlueInteractiveSession API is suddenly generating higher costs.

The How chart shows that GlueInteractiveSession costs can happen irrespective of Jobrun costs. Indeed – on June 03 there were no Jobrun costs. So running Glue ETL jobs isn’t causing these charges.

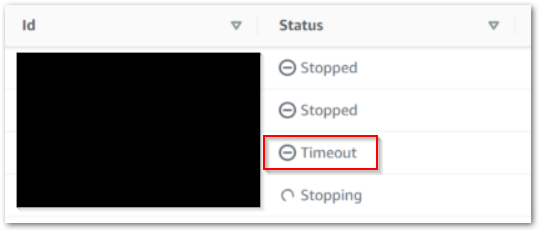

Helpfully, the AWS Glue console has a dedicated Interactive Sessions section that shows session instance histories. Upon inspection, I found lots of this:

So, timeouts. Timeouts are good. They stop Interactive Sessions from running indefinitely, and sessions started from the Glue console automatically get a 30-minute timeout.

What was more concerning was the number of timeouts I found: three on June 02 and six on June 03. That’s nine sessions, each of which timing out after 30 minutes. That’s four and a half hours of unused compute I’m being billed for! How are these timeouts happening?

…About that. I often open multiple browser tabs to compare screens quickly when I’m trying things out. Here, each new Glue ETL Job browser tab starts a new interactive session based on my commands, and I forget to close these sessions afterwards. Oops!

Solutions

So now I know the cost’s root cause is my own ineptitude, how do I fix this? There are several options:

Permission Blocking: I could deny CreateSession requests using IAM and SCPs. This solution works for non-data-facing AWS accounts but creates unreasonable barriers for Glue-based console workstreams elsewhere.

Parameter Adjustment: The CreateSession API has an IdleTimeout parameter that controls the number of minutes when idle before the session times out. Although this can be easily configured through the CLI or SDK, I haven’t found a way to adjust it in the console yet.

Local Sessions: AWS maintains a Glue Labs Docker image intended for local AWS Glue job script development and testing. This would replace the cloud-based Interactive Sessions entirely and is arguably the best solution for data teams and at scale. The main reason I’m not using it here is that I’m the only user of this particular AWS account.

Event-Based Automation: All Interactive Sessions are stopped using the StopSession API regardless of reason. This includes the timeout process. An automated mechanism that invokes this API after a set period would effectively emulate a timeout. Additionally, since I oversee this process, I’m able to swiftly adjust the duration as needed.

And so I finally have a user story:

As an AWS account owner, I want Glue interactive sessions to stop automatically after a chosen duration so that I don’t accidentally generate unexpected and avoidable costs.

Finally, there is one further topic I want to address…

Event-Based Vs Event-Driven

Let’s examine the difference between event-based and event-driven. Mainly because I thought this was an event-driven process for months until I did some digging.

Now, I’m no expert on this. However, James Eastham is. Go watch this. It’s only six minutes – I’ll wait.

Ok good. For those who are time-strapped or want the highlights:

- Event-based systems are technical events. Represented in a data context as API calls like ObjectCreated and CrawlerStarted.

- Event-driven systems are business events. Represented in a data context as processes like Refresh Started and Sales Data Ingested.

My Glue Cost Control system is event-based because it is governed entirely by AWS events and API calls: StartSession will trigger some AWS automation that ultimately invokes StopSession.

So what does that automation look like? Well…

Architecture

This section examines the decision-making and technical implementation of my AWS Glue event-based cost control architecture. In my investigations, I discovered that AWS is way ahead of me!

Existing AWS Solution

The AWS Big Data blog has a 2023 post about enforcing boundaries on AWS Glue interactive sessions using this architecture:

The whole process is listed here, and the post’s code is in a GitHub repo. In summary:

- The Glue Interactive Session creates a CloudTrail Event Record.

- An EventBridge Rule captures the event and invokes a Lambda function.

- The Lambda function inspects the event and acts depending on set boundaries.

- SNS handles user notifications.

- SQS and CloudWatch handle errors.

I’m using this architecture as a basis for my event-based Glue cost control process with some changes.

Architectural Decisions

This section outlines my adjustments to the AWS architecture to better align with my event-based Glue cost control process.

Replace Lambda With Step Functions

The AWS solution uses a Lambda function for event inspection and API interaction. This function has lots going on. But my needs are far simpler and fall well within the remit of a Step Functions workflow.

Many AWS heavyweights evangelize Step Functions over Lambda. Most recently, Eric Johnson dedicated a slide of his 2024 re:Invent session to this mantra:

“Step Functions first,

Step Functions always.”

For this use case, I’m inclined to agree. Step Functions offers several advantages over Lambda here:

Service Integration: Lambda’s interactivity with other AWS services requires manual code (e.g. a Python boto3 client). Step Functions offer no-code AWS service integrations that interact directly with AWS APIs. So my Step Function will be faster to develop.

Error Handling: Lambda relies on the function code for error handling and retries. In contrast, Step Functions offer configurable built-in no-code error handling and retry mechanisms, making my Step Function more resilient.

Ongoing Maintenance: While AWS manages the Lambda service, the function code still needs runtime maintenance, security patching and general refactoring as it ages. Conversely, Step Functions use static JSON and YAML-based ASL, so my Step Function will require less ongoing maintenance.

Step Function Model

There are two Step Function models: Standard Workflows and Express Workflows. I’ll be using a Standard workflow here. Two factors drive this decision:

API Behaviour: Changing a Glue Interactive Session is not an idempotent action. Requesting a change to a session in an invalid state produces an IllegalSessionState exception. For example, the below error is thrown when trying to stop a Glue job that hasn’t yet been fully provisioned:

{

"cause": "Session is in PROVISIONING status (Service: Glue, Status Code: 400, Request ID: null)",

"error": "Glue.IllegalSessionStateException",

"resource": "stopSession",

"resourceType": "aws-sdk:glue"

}Express Workflows utilize an at-least-once model, meaning an execution might run multiple times. Sending several requests that are very likely to fail will create confusion and waste resources. In contrast, Standard Workflows adhere to an exactly-once model with optional retries, significantly reducing the likelihood of these problems.

And speaking of resource use…

Cost: Express Workflow executions are charged according to how often they run, the duration of each run and the memory consumed during the process. Standard Workflow executions are billed based on the number of state transitions and feature a generous and indefinite free tier.

Standard Workflows are a better option here because my workflow requires waiting. While Express Workflows may not be too costly, I’d still be paying for the wait. And remember – the whole point is to reduce avoidable costs! Conversely, Standard Workflows would stay entirely within the free tier at the expected volumes.

Remove The SQS Queue

I’ve removed the SQS queue simply because I don’t need it here. It was originally intended to record events that triggered a Lambda function failure. However, the Step Function workflow’s inbuilt auditing will now capture this.

Considering the Frugal Architect Mindset and AWS Well-Architected Framework‘s Cost Optimization Pillar, the SQS queue’s financial and development costs are no longer justified. This cements its removal.

Architecture Diagram

This is my event-based Glue Cost Control process architecture diagram:

In this solution:

- User interacts with a Glue ETL Job and creates an Interactive Session.

- Glue

CreateSessionevent is created. - Glue

CreateSessionevent creates a CloudTrail event record. - EventBridge matches the event record to an event rule.

- Eventbridge extracts the event’s

SessionIDand passes it to the Step Functions workflow, which waits for the set duration. - Workflow passes

SessionIDto the GlueStopSessionAPI. This action retries twice if it is unsuccessful. - Finally, Workflow triggers an SNS email confirming the session’s stop.

Additionally, several services send logs to CloudWatch and gain permissions using IAM. If the Step Function fails, a CloudWatch alarm triggers a user email.

Summary

In this post, I examined some unexpected AWS Glue costs and designed an event-based cost control process architecture.

Once I understood the problem clearly, I iterated on an existing AWS architecture to build my bespoke event-based process. My architecture diagram shows how the key components work together and provides a clear implementation roadmap. In the next post I’ll start the build!

If you found this post helpful, the button below will take you to my contact details, socials, projects, and sessions.

Thanks for reading ~~^~~